5 psychological biases used in marketing

Cognitive biases are repetitive mistakes your mind makes when judging, evaluating, remembering, or making a decision. These mistakes are not unique to you, nor are they simply common. They are built-in our minds the same way our instincts are. They are the shortcuts that evolved so that we think less. Not because nature is cruel like that, but because it takes too much energy to think, and it would take so much more if we thought things through the way we do when trying to answer a math question. Also, we’d probably go insane.

It’s important to know about cognitive biases for a number of reasons. First, just for yourself. Knowing your cognitive imperfections and imperfections of other people makes you better in making judgements, decision-making, voicing opinion, etc. I know this might not sound like your life goal, but it does bring you closer to understanding reality the way it really is. Second, it helps to understand all ways in which you’re being manipulated as a consumer, because no one uses cognitive biases as effectively as advertisers, politicians, and others that aim to persuade. Third, it shows you the ways to improve your own attempts at selling your products or your ideas.

This post contains a list of such biases, not a complete one, mind you, but the biases that I find interesting and that haven’t been covered on this blog before.

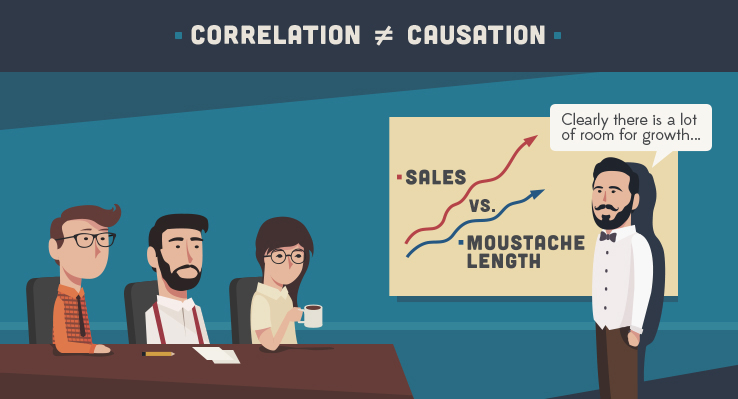

1. The effect of causality

As a marketer, you’ve probably heard a myriad times that stories sell better than facts. You can drown your prospect in numbers, but they won’t care until you present a touching and emotional case study that shows success with a real-life (or not so much) example.

The effect of causality is one of the reasons why this happens. We’re wired to see cause and effect everywhere, even if we know, or should know, that events aren’t connected. While it was believed for a while that we see cause and effect because of our vast experience with it, it’s been recently discovered that even babies of six months seek this pattern. They act surprised if the sequence is broken: for example, if the object hit another one and the latter didn’t move. But we take our preference for a smooth cause-effect story to the next level: if the object didn’t even touch a second one, just came close to it, and the second one started moving, we feel like the first object “launched” the second one.

We also believe strongly in intentional causality - things don’t just happen, they happen as a reaction to something. In one quite old study, the researchers made a clip, in which you see a large triangle, a small triangle, and a circle moving around. The story of the relationships and characters of geometric figures was irresistible: the large triangle was moving aggressively, it was coming dangerously close to the smaller triangle - obviously bullying it; the circle was moving in a terrified way. Only people with autism did not see any of this. And of course, the whole connection and character and relations were just in the viewer’s head, a head that’s so eager to see causes of behaviors.

A strong belief in causality is behind conspiracy theories. You might’ve noticed that they tend to connect many things at once and strive for the idea that a single factor causes multiple effects. In your everyday life, implicit causes and effects are in headlines, ads, all kinds of media. How often do you see clickbaits, such as “Gwyneth Paltrow is in the latest photoshoot. She looks gorgeous and says she hasn’t eaten meat since she was twelve!”

You know these two don’t have to be connected, but your mind jumps to make a cause-effect inference. Moreover, after reading something like this, you’re more likely to recall the word “vegetarian” than the words “photoshoot”, even though the latter was explicitly written, and vegetarianism was only implied.

Everything that proposes cause and effect sticks in your brains for longer.

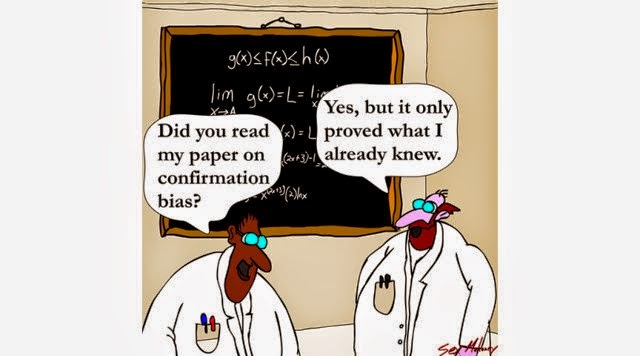

2. The confirmation bias

Confirmation bias has been widely discussed in the media following major political incidents such as the election of Donald Trump and Brexit. How did it happen that all political predictions were wrong? Why would Facebook or Google or Russian hackers be responsible for whoever people voted for?

You might’ve heard the term “echo chambers”: social media communities that reinforce and amplify beliefs by communication and repetition inside a closed system. Every social media platform has such: Facebook groups, Twitter pages, Reddit’s subreddit ( only /r/changemyview/ seems to be an exception). Moreover, Facebook recommends groups similar to the ones you’ve joined or the ones joined by your friends (most likely, holding the same social and political views as you do), Twitter does the same, and Google learns your preferences, adjusts search results to show you the pages similar to what you’ve searched for, takes into account all geographical and other info it has on you, and, for example, shows Crimea as Ukrainian territory to Ukrainians and as Russian to Russians. All that is the result of machine learning and narrow AI that is Google search.

Our mind works in a vaguely similar way. It seeks, finds, and delivers information that confirms or amplifies the beliefs we already have. This is less expensive (in terms of self-preservation and energy) than to get confronted with new ideas, process them, and reconstruct one’s worldview (or deeply held opinions on the best yogurt) every time. This is called the confirmation bias.

How does it apply to marketing, you might ask. Application depends on what you know about your target audience. If you know them well, feed them information they already suspect to be true. It’ll win their loyalty and set up a spiraling sequence of agreements.

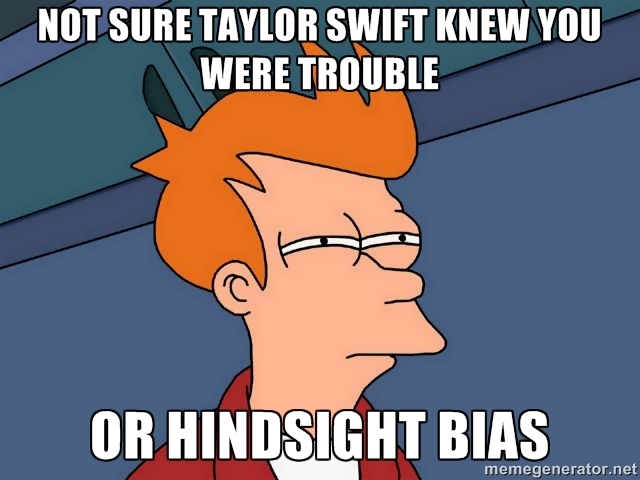

3. The hindsight bias

Our mind is ridiculously self-serving (unless you’re suffering from mental illness). In most cases, it believes that you’re the one who is right about everything and every other opinion is not quite that right. But what can one do, if you’ve had an opinion, and then were faced with a fact that you couldn’t ignore, and your opinion had to change? Or, what if you simply evolved into a person with a different view for whatever reason? Should your mind despise the “you” from yesterday?

No, it rather forgets. And that’s what the hindsight bias is all about. Its ability to remember past states of knowledge and beliefs is imperfect, to say the least. When asked to reconstruct their former beliefs, people retrieve their current ones instead. Many cannot believe that they ever felt differently.

How often have you heard people say “I knew it’s going to happen!” about the most unexpected events? No, they didn’t. But they’re not lying: their minds can’t go back to the not-knowing state, and, therefore, conclude they must’ve predicted the event.

In one study, researchers conducted a survey before President Richard Nixon visited China and Russia in 1972. Many outcomes of this event were rather unpredictable. The respondents assigned probabilities to fifteen possible outcomes of Nixon’s diplomatic initiatives. People stated their predictions about Mao agreeing to meet up with Nixon, U.S. granting diplomatic recognition to China, agreements made between U.S. and Soviet Union, etc. in a form of probability (i.e. “How likely is X to happen on a scale from 1 to 5).

After Nixon returned, researchers asked participants to recall the probability that they had originally assigned to each of the fifteen possible outcomes. If an event had actually occurred, people exaggerated the probability that they had assigned to it earlier. If the possible event did not happen, the participants erroneously recalled that they had always considered it unlikely.

The hindsight bias might seem relatively innocent but it’s far from it. The hindsight bias ensures that you judge everything by its outcome. For example, there’s a low-risk surgical intervention in which an unpredictable accident occurred. The jury will be prone to believe, after the fact, that the risk was bigger than it actually was, and that the doctor who ordered it was to blame.

Or imagine a more marketing-friendly scenario. You read about a strategy that works 20% of the time, according to the experts. You decide to try it anyway, and suddenly it works. This triggers the dangerous “I knew it all along!” feeling. You sell that idea to the boss, get your budget, and go on creating campaigns happily. The second time the strategy doesn’t work. Nor does it the third and fourth times. You panic, you try again. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t – 20% of the times or so.

The lesson here is: don’t overestimate your abilities. No, you can’t predict the future and you couldn’t do that earlier. Don’t revise the odds because of the outcome. Trust the stats and nothing else.

4. The Endowment Effect (i.e. the Ownership Effect)

Humans are loss averse. That is, losses hurt more than equivalent gains feel good. At least, that’s what decades of research show. Unlike what you might’ve heard from numerous wise people, we love and value what we have, especially when reminded that we might lose whatever it is. This leads to the ownership effect – we assign a bigger price to things we own than we would if we didn’t own them. You’ve probably noticed this from your personal experience. Ever wished to sell a car? A flat? A dress? Thought people were just too greedy to pay the price the object was definitely worth?

A large number of studies were conducted to show the endowment effect in different contexts. For example, students would not trade a coffee mug they had been given for a bar of chocolate, even though when asked about their preferences, they rated a coffee mug and chocolate equally. But they already owned the coffee mug and that changed everything.

In a similar experiment, mugs that costed around $6 were distributed randomly among participants. They had university logo on them and looked quite attractive. Both owners and participants that didn’t have the mug - “buyers” - indicated the price they would pay for a mug. The average selling price was about double the average buying price. The number of trades was less than half of the number predicted by standard economic theory - you know, the one that assumes that we are rational human beings and wouldn’t rate cups differently depending on whether we have them in our hands or not.

There were many, many more studies. In some (on basketball tickets), the difference between selling price and buying price could go up to 200%. Context, items, market price or anything else didn’t affect the endowment effect. Only time did: participants had to own the item for a while before the possibility of trading was suggested.

In marketing the endowment effect is used often and effectively. Take free coupons, free trials, test drives and products with some free balance. This creates a sense of ownership right from the start. You become the person who uses the service, drives the car, etc. You’re not willing to give that up.

5. The Certainty Effect

And the last one for today - the certainty effect. The gist of the certainty effect is this: the improvement from 95% to 100% becomes a qualitative change and, therefore, has a much larger impact. For example, if your chances of winning whatever rise from 90% to 95% that won’t affect your behavior. However, if it rises from 95% to 100%, it definitely will. This seems logical even though we do realise that the difference is virtually the same. But consider this example, taken from Kahneman’s work:

“Imagine that you inherited $1 million, but your greedy step sister has contested the will in court. The decision is expected tomorrow. Your lawyer assures you that you have a strong case and that you have a 95% chance to win, but he takes pains to remind you that judicial decisions are never perfectly predictable. Now you are approached by a risk-adjustment company, which offers to buy your case for $910,000 outright—take it or leave it. The offer is lower (by $40,000!) than the expected value of waiting for the judgment (which is $950,000).”

Are you sure you would reject it?

Rationality says yes, certainty effect says no. I’d bet on a certainty effect.

As Kahneman also points out, a large industry of “structured settlements” exists to provide certainty at a hefty price. I’d add that in marketing, you can notice how the certainty effect is used when brands offer “100% money back guarantees” and the like. Generally, the more you can reassure your customers that there’s no risk of any kind when buying your product, the more chances you have of persuading them. Think about it: “95% money back guarantee” wouldn’t work like magic, even though it does mean you give back money to nine and a half people out of ten :)

Any thoughts on the topic or biases you’d like to be covered (or explained in more detail)? Let me know in the comments!