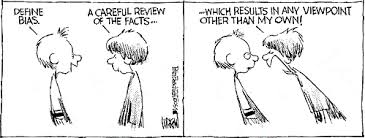

3 biases that affect buying decisions (or how psychology can boost your revenue by 42%)

Everything is relative. If you don’t know the price of, say, a pearl, you can’t possibly imagine it. For all you know, it could be $20 or $20,000. And what about a black pearl? Should it be more or less than the white pearl? 20 times more or 20 times less? We can’t say. We have to find out the market price for pearls first, and for black pearls, second. Similarly, if an alien comes to planet Earth, and sees a human being of 6’7, he won’t be able to say whether it’s a tall human or a short human. I could carry on but I’m sure you got the point.

To understand the environment around us, we need information. Our brain seeks it all the time, desperately trying to make sense of every situation. Attempting to gather as much as possible and analyze the situation as quickly as possible, it makes our judgement prone to mistakes. Here we’ll explore these exciting mistakes and draw some conclusions for marketers as well as other interested individuals.

The contrast principle

As we’ve recalled before, decisions aren’t made in isolation. Whether it’s price, height, or anything else really, we need context to evaluate whatever is given. Some context is gathered with experience (we’ve seen enough people to identify tall and short ones), some context has to be provided immediately (if we’ve never bought an antique chair and now we want one and it’s $500). In both cases we’ll be affected by the contrast principle, albeit to a different extent. This can be observed in purely physiological responses: if we lift a light object first and then lift a heavy object, we will estimate the second object to be heavier than if we had lifted it without first trying the light one.

This phenomenon applies to all areas of our life. If we are talking to a beautiful woman at a party and are then joined by a less attractive one, the second woman will strike us as less attractive than she would if we’d seen her alone.

The contrast principle is heavily applied in sales. Surely, those discounts spring to mind first. But what about simply overpaying for expensive things, noticing the problem but not caring at all in the context?

For example, the research shows that people would go across town to save $7 if they’re buying a pen for 25, but not if they’re buying a suit for $455. It seems logical even, doesn’t it? Not really: $7 don’t change its value from case to case.

What about buying additional products? Another study showed that a man might balk at the idea of spending $95 for a sweater, but if he has just bought a $495 suit, it’s very likely he’ll buy the $95 sweater.

Do you recall cases from your own background, in which you fell victim to the contrast principle?

Before we get into marketing takeaways, which I’m sure pop uncontrollably into your mind at this point, let’s explore the contrast principle in its full power.

P.S. All mentioned studies taken from the book based on the research by Dan Ariely: here's a helpful outline.

Anchoring

Anchoring describes the people’s tendency to rely far too heavily on an initial piece of information (known as the "anchor") when making decisions. After you’ve seen, say, price A, everything that comes after it (prices B, C, D) will be adjusted in your mind to price A. Not to the market price, which you might be perfectly aware of, not to the average of A,B, C, and D. And prices are not the only domain where this happens. Once the value of the anchor is set, all future negotiations, arguments, estimates, etc. are discussed in relation to the anchor.

In a classic study by Tversky and Kahneman, researchers asked participants to provide an estimation of the percentage of African countries in the United Nations using randomly generated numbers provided by a wheel of fortune. Imagine yourself in a participant’s place. The wheel of fortune is given a spin, the needle lands on 65. Your question will be:

Is the percentage of African countries in the United Nations greater or less than 65?

Well, you think, less than 65% for sure.

Alright, the researcher says,

What is the exact percentage of African countries in the United Nations?

I won’t try to guess your answer at this point, but the most common one is that it’s 45%.

Now imagine that now you are another person, a person who has not yet answered any questions about the United Nations. In fact, you’re Johny from Louisiana, your girlfriend is in love with your best friend Mark, and you want the world to be a better place.

The wheel of fortune is given a spin, the needle lands on 10.

Is the percentage of African countries in the United Nations greater or less than 10?

Well, it’s definitely more than 10%.

So what is the exact percentage of African countries in the United Nations?

The most common answer in this case is 25%.

Have you noticed what just happened? The difference between two responses is almost double, while the anchor was a wheel of fortune - a completely, knowingly random number!

This is a bit on how anchors work with general knowledge. How does it work when money is involved?

In another Tversky and Kahneman study, researchers asked students to recall the digits of their security numbers. They then asked the students to bid on a cordless keyboard.

Result: the students with the highest-ending social security digits (from 80 to 99) bid highest, while those with the lowest-ending numbers (1 to 20) bid lowest. The top 20 percent bid an average of $56 for the cordless keyboard; the bottom 20 percent bid an average of $16. This is a ridiculous difference! More precisely, researchers reported that the students with social security numbers ending in the upper 20 percent placed bids that were 216 to 346 percent higher than those of the students with social security numbers ending in the lowest 20 percent.

The anchoring effect remains robust in legal judgments, purchasing decisions, negotiations, etc.

The role of anchor relevance & magnitude

A number of modern researchers tested the magnitude of the anchoring effect with anchor relevance, but failed to find a difference. As strange as it is, seems that the anchoring effect does not depend on the informational relevance of the anchors.

What about the size of an anchors? If you’re trying to sell a coffee maker for $50 instead of $30, should you first expose a customer to a TV that costs a $100 or $1,000? So far, it seems that extreme anchors lead to larger anchoring effects, but results are not conclusive at this point.

The role of the expertise (spoiler: non-existent)

Plenty of research attempted to show that people that are experienced in a given field are not subjected to such arbitrary biases. But that’s not true. Car mechanics and car dealers with all the necessary information, estate agents, experienced legal professionals - all were significantly influenced by irrelevant anchors on their decisions in their own fields. What’s more, the findings also showed that they mistakenly see themselves as less susceptible to the anchoring effect, which might be making them more prone to them. However, it’s also undeniable that as in any case individual differences exist and anchoring does not affect each person at the same level.

The role of intelligence (spoiler: not significant enough)

Alright, here’s something different. Researchers found that anchoring decreases with the higher cognitive ability. However, anchor values are still significant in the high cognitive ability group.

The role of awareness (spoiler: non-existent)

In the awareness questionnaires, the majority of people claim they haven’t been influenced by anchors, which only proves that it’s a subconscious process that you can’t spot. However, even when people were warned about the anchoring effect beforehand, it wasn’t reduced.

Marketing takeaway:

Anchoring is widely used in marketing. It makes customers feel like they’ve got a bargain. All you have to do is provide the initial point of reference for all other options.

For example, the first cars the dealers will present - the ones you see even while passing the place - are the most expensive ones. After seeing these ridiculous prices, you’re much more likely to get a much cheaper, yet still overpriced, used car.

Another example: it’s widely known that people often choose the second most expensive bottle of wine in a restaurant (not to look cheap, perhaps). Therefore, it’s common to have the first one heavily overpriced, and the second one less overpriced - the chances your customers buy the second one will skyrocket. Same goes with other items on the menu (takeaway leaflet, online subscription, etc.): inflate the prices for the first item/page, and the others will sell better.

As we know that anchors don’t have to be relevant, it gives us complete freedom in using them. Trying to sell a hotel room twice more expensive than it actually is? Make website users watch an ad for a flight to another continent first.

Or take the negotiation process. In most cases, an initial offer may serve as an anchor to assimilate the final judgment toward it. Even if the negotiators are aware of the effect, it won’t stop them from falling victim to it.

The idea is always the same, but the opportunities are plentiful.

The decoy effect

Not so long ago, The Economist had a number of subscription options that looked like this:

Which one would you choose?

Dan Ariely decided to ask his students this question and discovered the following: predictably, nobody chose the print subscription alone; 84% opted for the combination deal, and 16% for the web subscription. Then he took another class as a sample and repeated the poll without offering the unpopular print-only alternative - after all, nobody was choosing it, so what difference could it make to leave it out? However, something great and intriguing happened: this time around 32% wanted the print subscription, while 68% preferred to go web-only.

What is this magic? It’s the decoy effect - another cognitive bias that plays on the contrast principle. The decoy effect occurs when you have choice A, choice B and you add choice -B (minus B) - a completely unattractive choice that contrasts well with one of the good choices.

For example, you’re asked to choose between a five-star restaurant, which is a 25 min drive away and a three-star restaurant, which is 5 min away. They are pretty much equal in their value. So two experiments took place. When the researchers added a four-star restaurant with a 35 min drive to the choice set as a decoy, the result showed that the participants tended to prefer the five-star restaurant that was 25 min away. However, when the decoy was a two-star restaurant 15 min away, the result showed that the participants' preferences had switched to the three-star restaurant 5 min away. In both experiments the third unattractive option was used to never be chosen and act solemnly as a boost for one of the options.

This effect is one of the most robust biases in consumer choice. Industries ranging from chocolate bars or beer to TV-sets have employed this instrument.

Marketing takeaways:

For example, the decoy effect is used heavily in real estate. Quite often some flats or houses would be shown to act as a decoy - to show you how terrible the living conditions could be - so that another house can be pushed. Obviously, this isn’t the only industry that can employ the technique - it’s available to almost any industry.

In another nice example from the 90s, Williams-Sonoma introduced a bread maker for $275. No one would buy it: people weren’t sure they needed a bread maker and there were so many other things to buy in the shop. To push the bread maker, the company introduced a slightly better, bigger bread maker and priced it twice as much. Predictably, sales took off for the original bread maker.

What does this teach us?

People live by comparing things. If something isn’t being sold - give them an initial reference point, a worse version of whatever isn’t being sold, and you won’t believe the results.

Any questions or comments? Leave them below - I’ll be more than happy to reply to every reader. Liked the article? Please share it with your followers - let’s spread the knowledge together!