How our mind works (or why we judge so many things wrong)

I’ve got a confession to make. This post is largely based on Kahneman’s “Thinking Fast and Slow”. I adore this book, and I believe not enough people have read it - so if you did read it and don’t feel like you need a reminder, go ahead and check out anything else on this blog.

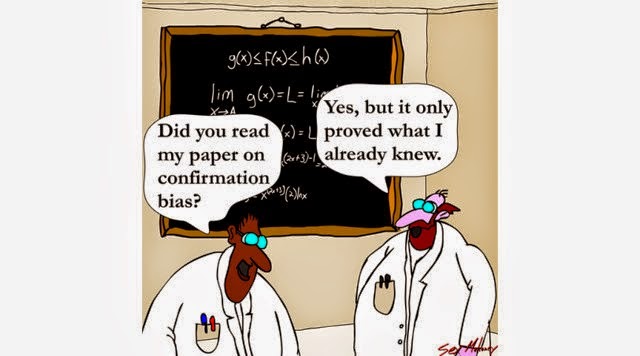

For the rest, this is going to be one of the most eye-opening blog posts ever. You’ll realize, at least I hope you will instead of disregarding all of this and moving on, that so many of your judgments regarding your business, your buying behavior, and indeed the world you live in are terribly wrong. And even if after finishing the post you’ll fall into the trap of the confirmation bias and tell yourself “that’s pretty much how I thought it works anyway”, I’ll feel like my job here is done.

Let’s start with a question that shows well about how we judge things around us when we take time to think for a bit.

An individual has been described by a neighbor as follows:

“Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.” Is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer?"

The absolute majority replies with “a librarian”. Why? Well, the personality description speaks for itself, doesn’t it? He probably wouldn’t consider a farmer job having all these traits, he probably wouldn’t be happy being one… What didn’t come to your mind when you were making the judgment?

Statistics.

Surely, you know that there are far more farmers than librarians, and if you take that into account, you'll realize that poor Steve has very little chance of being a librarian. But you didn’t think about that, you considered the situation in a vacuum, as if what you see - what is given - is all there is.

This is called the base-rate neglect. In short, people use what little information is given to them and don’t take statistics into account when making a judgment.

Here’s another one for you. This is a very real case:

A study of the incidence of kidney cancer in the 3,141 counties of the United States reveals a remarkable pattern. The counties in which the incidence of kidney cancer is lowest are mostly rural, sparsely populated, and located in traditionally Republican states in the Midwest, the South, and the West.

Why?

You may be a bit wary now of jumping to conclusions. And you’d be right. As witty statisticians Wainer and Zwerling who popularized this example, said: “It is both easy and tempting to infer that their low cancer rates are directly due to the clean living of the rural lifestyle—no air pollution, no water pollution, access to fresh food without additives.”

That is until you learn that:

The counties in which the incidence of kidney cancer is highest are mostly rural, sparsely populated, and located in traditionally Republican states in the Midwest, the South, and the West.

Here, statisticians also comment: “It is easy to infer that their high cancer rates might be directly due to the poverty of the rural lifestyle—no access to good medical care, a high-fat diet, and too much alcohol, too much tobacco.”

The answer is this: rural counties have a small population. The facts above are statistical facts: they change the probability of the event, but they don’t cause the event. The small population of a county merely allows the incidence of cancer to be much higher (or much lower) than it is in the larger population due to the rules of statistics.

Complete lack of statistical awareness is just an example of how we perceive the world. The bigger picture is this: when faced with a situation (a question, a task, an ad, a person, etc.), we judge the situation based on the content we’re given as if it exists in a vacuum. As a result we live with a simplified and more coherent view of the world around us. We don’t consider the reliability of what we’re given as long as it makes a good, coherent story.

A number of biases that you’re subjected to in your everyday life and that are heavily used in marketing are a result of that overwhelming simplification.

Availability heuristic

Consider the following question:

“Mindik is intelligent and strong. Will she be a good leader?”

The answer that quickly comes to mind is “yes”. In fact, it comes to mind before you were even aware of it. How did that work? Your mind jumped to a conclusion based on the information available at hand. Before going “yes”, it didn’t consider that Mindik could also be cruel and corrupt, for example.

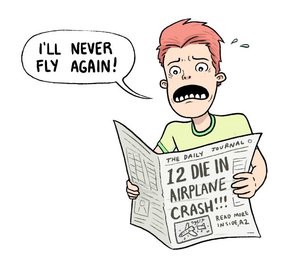

The essence of the availability bias is that if retrieval is easy and fluent, the category will be judged to be large or judgments will be based on the information that is easily recalled.

You’d think that if you were just given the time to consider these questions, you’d be more objective. Unfortunately, research shows that's not true. In most cases, people rationalize their opinions - the ones that have been initially formed due to the availability heuristics, if they’re given the time to think.

For example, here's a question:

Who is more likely to cheat on their partner: a physician or a politician?

First, you think, politician, surely. It’s an intuitive answer that comes to mind readily because adultery among politicians is covered much more often than that of physicians.

If you take time to consider your opinion, you’re more likely not to change your mind, but to “find proof”. For example, you might think that politicians have all the money and power, and that makes them less likely to stay faithful.

At the same time, if you’ve got a couple of friends who are physicians and who cheat on their partners, your answer and its justification will be completely different, because you’ll recall their cases prior to thinking of what you’ve read in a newspaper a month ago. Neither the media coverage nor your friends are real proof, of course.

As if our mind wasn't irrational enough already, here're the factors that affect people in a way that makes them even more susceptible to the availability heuristics:

- when they are engaged in another effortful task at the same time

- when they are in a good mood (e.g., because they just thought of a happy episode in their life)

- if they score low on a depression scale

- if they are knowledgeable novices on the topic of the task, in contrast to true experts

- when they score high on a scale of faith in intuition

- if they are (or are made to feel) powerful

Some of these factors are easily manipulated in marketing conditions. For example, much of advertising is done to have you recall some allegedly happy moments of your childhood, and much is done to make you feel powerful.

Overconfidence

We’re used to trusting experts, and we’re used to trusting people that are confident in what they say. What we should stop and think about is, though, where does confidence come from? You’d think knowledge and experience. You’d think the quality and quantity of the evidence for what they say. You’d be very wrong.

The confidence that people have in their beliefs depends mostly on the quality of the story they can tell about what they see. As we know, that works even if they see very little.

Marketing takeaways:

- Make any information that would simplify the decision-making process easily available on the site, on your social media platforms. Tell your visitors straight away about the problems your product solves, include customers’ testimonials, include social proof and any achievements. Talk about why you’re a better choice than your competitors.

- When selling your product, your goal as a marketer is to tell a coherent story of how your product helps solve a problem that a customer faces. The story should be flawless and not necessarily logical in the bigger picture. If you’re facing problems proving the success of your company/product, show your clients a couple of representative examples in addition to all the numbers and graphs. You can’t change people’s perception of something with statistics and objectivity, but you can do that with examples.

- Work on brand awareness through all methods available to you, even if at the moment it doesn’t seem to bring results.

Regression to the mean

This brings us back to the beginning of the post. How do we judge the situations around us? How do we know what happened and what to expect? What do we always neglect?

Statistics.

Regression to the mean, another statistical concept, is something I am very eager to tell you about. And in case you do know about it, a reminder is also a good thing, because as human beings we tend to disregard counterintuitive, abstract concepts and go with a good story. So, let’s get to it.

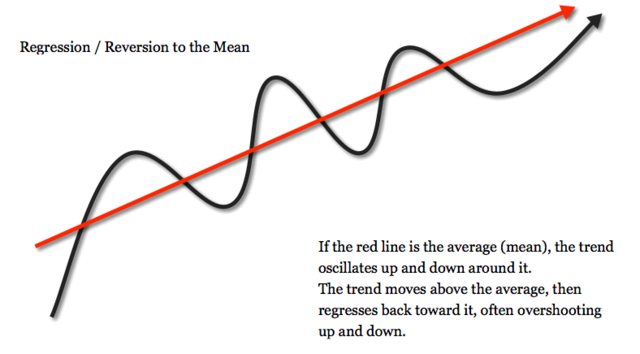

Regression to the mean is the phenomenon that if a variable is extreme on its first measurement, it will tend to be closer to the average on its second measurement, and if it is extreme on its second measurement, it will tend to have been closer to the average on its first. Could be like in the following picture, however, the line could stay the same or decrease, depending on the overall trend.

For example:

If your parents are taller than average, you won’t be taller than your parents - you will be tall but closer to the average. If the performance of your company has been outstanding last year, this year won’t match it - it will be closer to the average performance of your company. The example that is often given because it seems tricky is this: "Most very intelligent women marry less intelligent men. Why?" The answer is: no cause. It’s a merely statistical fact. Similarly, because we tend to be nice to other people when they please us and nasty when they do not, we are statistically punished for being nice and rewarded for being nasty. Think about it: someone has been extraordinarily nice to us. We notice that (we wouldn't notice the average niceness) and act nice to them, too. And after that the person goes back to their average self. We're left disappointed and frustrated - it seems that their behavior is a reaction to ours. Same works when someone has been a, uhm, not a good person. And all of this is, again, a merely statistical fact. Statistics works in every field, from evolutionary biology to human relationships to businesses.

Regression to the mean isn’t a thing used a lot in marketing, nor can it be used. However, it’s something that is crucial to understand when you judge your employers, yourself, your marketing campaigns, traffic, sales, results - anything. It’s something to keep in mind, especially in a business context.

So, my last question is this: have you learned anything new? Will you be a bit mindful of your judgments or does this seem irrelevant to the way you think? Do you have some ideas to add? Let me know in the comments!