The Placebo Effect (in marketing & pricing)

The law of demand states that conditional on all else being equal, as the price of a good goes up, the demand for it goes down and, conversely, as the price of a good goes down, the demand for it goes up. And logic dictates that’s exactly what should be happening. But of course it’s not (at least, not all the time).

Einstein famously said that “reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one”. What if together with the price, the reality - the effect or experience one gets from the product - changes? What if apples genuinely taste better if bought for a higher price? What if the same energy drink suddenly gives you less energy when on discount?

Sounds like fiction? Maybe not so much.

The placebo effect

After all, we’ve all heard of placebo - sugar pills with no active therapeutic ingredients or sham surgical interventions. The placebo effect is a well-established phenomenon in medicine that shows that placebos induce the real effect on the patient’s well-being. The placebo effect is found in Parkinson's disease, neuropathic pain, headache, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, and so many other very real diseases and pains. The research showing the placebo effect is ongoing, as every clinical trial involves the placebo control group.

The mechanism of the placebo effect is attributed mainly to classical conditioning and expectations. These psychological processes produce neurological results (as we’ve discovered once the fMRI technology was introduced). For example, cocaine abusers show a different kind of chemical brain activity when they’re told they are given the drug; people suffering from depression show an activation in the area where antidepressants usually work; decaffeinated coffee activates the brain when the drinker isn’t told it’s decaf, and so on.

The combination of the person’s past experiences (doctors helped in the past, pills/drugs/coffee/ worked, etc.) and the expectations of getting better (these expectations cause hormonal changes as well as attitude and behavior changes) act as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Now let’s go back to marketing. And more precisely, to pricing.

The placebo effect and pricing

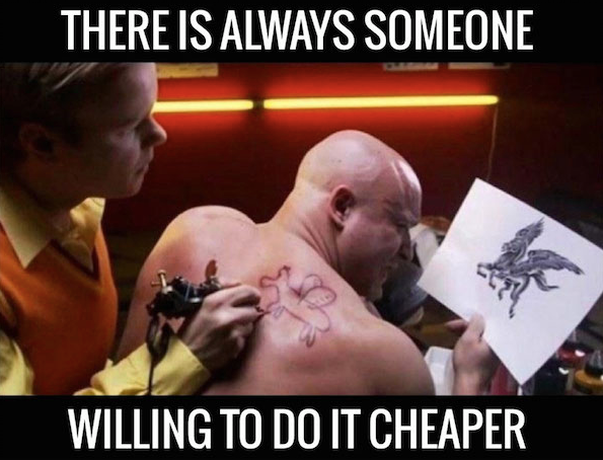

Dozens of empirical studies have shown the strong connection in people’s minds between price and quality. Despite many cases where this is plain wrong, people assume that “you get what you pay for”.

It might be that the price-quality belief drives expectancies that yield the self-fulfilling prophecy that expensive products will perform better than low-priced. In support of this view, a number of experiments were made.

In one, the researchers gave people a series of electrical shocks of varying magnitude and asked them about the pain they experienced. As you might imagine, the pain was very much present. Next, the researchers gave participants either a cheap pain reliever (vitamin C actually) or an expensive one. Then they repeated the shocks. The participants in the expensive placebo group reported that it worked pretty well, much better than the group who got the cheap placebo.

Another series of experiments showed that:

- A higher-priced SoBe reduced fatigue better than the discounted SoBe (and increased performance by 28%!)

- A discounted energy drink hindered the intensity of the workout compared to the regularly priced energy drink

In none of the studies, when asked during debriefing if the price played a role, not a single participant answered affirmatively. This tells us that the process is absolutely unconscious - just like in medicine.

As Dan Ariely put it, a 50-Cent Aspirin can do what a penny Aspirin can't, and that’s the greatest summary of the placebo effect in marketing.

Marketing takeaway:

While discounting and generally slashing the prices always seems like a good solution to increase short-term sales, it might hurt your sales in the long-term, as people will get less benefits from the discounted products and assume they are of lower quality. Conversely, rising prices for the items that don’t sell may suddenly increase sales, as customers will assume these are better quality, get more benefits from using the products, and come back for them later.

The pricing of luxury goods

While we’re on the topic of making products expensive, let’s talk about luxury products.

What is luxury to you? Give yourself a couple of seconds to come up with a definition.

Strangely enough, the idea of what makes a product (brand) a luxury has been debated in marketing literature with much interest and paradoxicality. Consumers and marketers mostly agree that price here is part of the definition. However, they can’t agree what price that is: for example, to a question “Under what price would you say that ring is not a luxury?” consumers respond with $1130 and to a following question “At what price would you say a luxury ring starts?” they respond with $1983 (source).

Being ‘expensive’ is the first criterion for qualifying luxury in Japan, the second in France, the third in China and Germany. The price here is supposed to reflect history, quality, legend, prestige - experiential and often illusory concepts that have a lot to do with the placebo effect.

Brands do a lot to keep up this effect. For example, each year Rolex increase their price systematically, without any objective reason (cost based).

But what if you want to attract new clients and widen your target audience?

Marketers agree that it is possible for luxury brands to sell cheaper product lines to attract new clients, but only if the brand is well-established and already strongly associates with luxury. It’s also suggested a brand should still keep more expensive and posh product lines, so that old customers could keep being in a more prestigious group than the new ones. This, for example, is how Armani was able to introduce Armani Jeans without losing its status.

Marketing takeaways:

If you’re a luxury brand entering the market, ignore the urge to introduce sales, discounts and cheaper products. Luxury doesn’t do sales - in this world, something can’t cost one thing today and another one tomorrow. Your prices should signify the entry into a different world, which is all about key brand values, the allegory for success, and the prices that are far above normal and in line with direct competitors.

Got any questions left? Let me know in the comment section and I’ll do my best to reply! Liked the article? Again, pleeease let me know, and I’ll keep writing more!