Too much choice and information: do they hurt your sales?

I have a friend who once came into a supermarket, saw a selection of two hundred cereals, and had a mental breakdown. “How am I supposed to make any decisions in life,” he told me, “if I can’t even choose a cereal box?”

While this might be a serious overreaction, it’s very understandable. Have you ever stared at a menu for far too long feeling completely lost? And then ordering something you were not very sure of, and then feeling like you could’ve done better? Or walked into a store thinking “Oh my God, so much good stuff in here!” and walked out with absolutely nothing?

In his Ted talk, psychologist Barry Schwartz tells how he wrote a book trying to explain to himself the following situation: he used to own a couple of rather uncomfortable pairs of jeans for decades. Once, he went into a store to buy another pair. He was faced with a huge selection and spent an hour trying on different jeans. After that, he walked out with the most comfortable pair of jeans he ever had. But he felt worse.

The question is: why?

The paradox of choice

From a very young age, most of us believe that the more choice - the better. While the benefits of some choice are absolutely clear, anecdotal evidence suggested long time ago that “too much” choice might be hurting people’s satisfaction, including product satisfaction, and hurting sales when it comes to businesses. Is that really the case?

Not at the first glance at least. Research, old and new, shows that marketplaces who offer more choice have a competitive advantage over those who offer less. Moreover, brands offering higher variety are thought to be of higher quality.

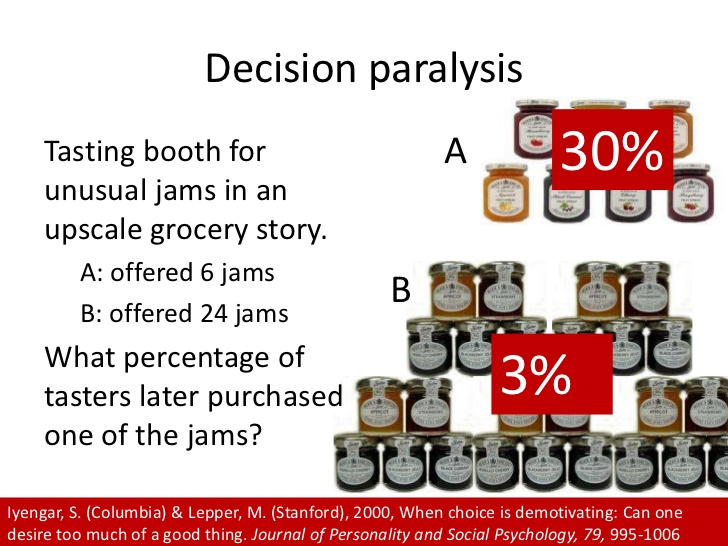

However, researchers are a suspicious bunch: they decided to test the “choice overload” idea. They set up a tasting table with exotic jams at the entrance of an upscale grocery store. In different parts of the experiment, the table had either a small assortment of 6 jams or a large assortment of 24 jams. Every person who approached the table got a discount coupon for a jam.

Results: more people approached the tasting table when it had 24 jams. However, 30% bought a jam when there were 6 jams, and only 3% bought a jam when the table had 24 jams. It’s 10 times the difference!

This was in a way in line with the previous studies: shops that offer more products attract more clients. But does that necessarily mean that they sell more?

The researchers were intrigued and continued the study. This time, they offered participants a choice between either 6 or 30 exotic chocolates. Participants who chose from the 30 chocolates said the experience of making the choice was more enjoyable but also more difficult and frustrating.

But the most interesting part is this: participants who had to choose from 30 chocolates reported less satisfaction with the chocolates they finally chose than those who selected from 6 chocolates.

Moreover, at the end of the experiment, only 12% of the participants from the 30 chocolates group accepted a box of chocolates instead of money as compensation for their participation, compared to 48% in the 6 chocolate group.

In my opinion, that’s where you make a direct connection with customer retention.

Results that hint that too much choice hurts sales and product satisfaction were also found in the studies involving pens, gift boxes, and coffee. Another study on undergrads showed that the quality of written essays decreased if the number of topics to choose from increased. Along the same lines, it was found that the number of 401(k) pension plans that companies offered to their employees was negatively correlated with the degree of participation in any of the plans.

Think about it: people preferred to pass on getting money from the companies and risked poor retirement just to avoid making a choice.

Why does this happen?

Choice paralysis

Making a choice is a difficult task. The more options you have, the more similar they get, the harder it is to justify to oneself you made the right one. You end up postponing the choice, and then postponing it again and again until you either forget or give up - the cognitive load just seems not worth it.

Product dissatisfaction

Choice paralysis is understandable. But why do we end up being less satisfied if we did make a choice?

When too much choice occurs, imagined alternatives reduce from the experience of the product we chose. As people value things in comparison to other things, we can’t see the product in a vacuum: we start comparing it with all the products we didn’t choose. If there were 5-6 alternatives, we can be quite sure ours is the most suitable one. However, if there were 30 alternatives, it becomes very hard to say. In this case, one can be sure the product was the best choice indeed only if it’s absolutely perfect. And what chocolate/cereal/research topic/pension plan is perfect?

Then self-blame comes in. After all, you had all the opportunities: what stopped you from making the perfect choice? The combination of these feelings makes us feel worse about the choice we made, which, in turn, might mean not coming back for the product.

Marketing application:

Alright, so what do we as business owners and marketers are supposed to do if more choice attracts more clients, but less choice makes them more likely to buy and come back for more?

First, it’s important to do all you can to simplify the choice-making process. Some ways to do that:

- Introduce the “optimal choice” or the “most popular choice”

- On your website, limit distracting Calls-to-Action

- Break down products by category: e.g., “Books to read on holidays vs Books to have on your desk 24/7”

- Keep in mind that your prospects shouldn’t feel overwhelmed

- Test for the optimal number of product choices (present 4 types of cakes instead of 10 in your coffee shop and see if that changes your sales - it might!)

Information bias

So, we now understand the situation with too much choice. What’s with too much information? Is that a thing?

Quite the opposite. While too much choice produces paralysis, providing customers with loads of information is a great antidote.

People tend to believe that the more information they have, the better. This is intuitively correct, unless we’re faced with the situation where people make decisions based on the amount of information, not whether this information is applicable. And that’s exactly what they often do, according to dozens of studies on information bias. For example, people would do additional expensive medical tests even though they are aware the results of the test wouldn’t affect the treatment (source).

Marketing applications:

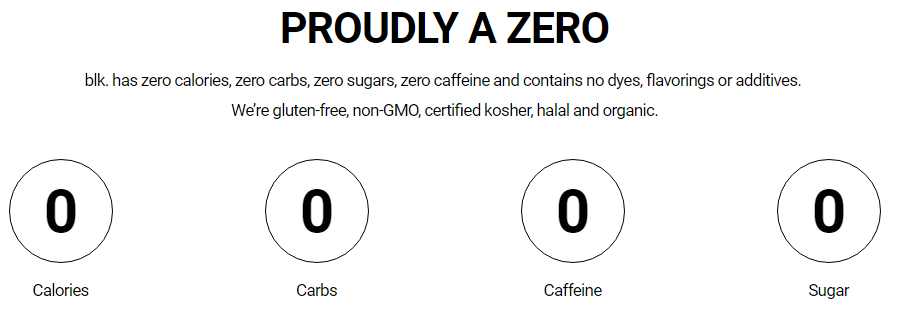

Ever wondered why food packaging involves more and more information? Sure, some of it is for you to eat healthier. Some, however, is just to provide you with an illusion that you’re making a smart decision. Oversupply of information is a great marketing tactic that every marketer should be aware of.

Hope this gave you some valuable insights into how our mind works and how to apply this knowledge to your marketing strategy. Let me know all your questions and opinions in the comments below!