Why people would rather work for free (with marketing takeaways)

As psychologists and anthropologists suggested long time ago, we live in two different worlds simultaneously: a world of social norms and a world of market norms.

The first ones includes doing something good for its own sake. You help your neighbour move in because it’s a nice thing to do and you make a dinner for your family on Thanksgiving without expecting your sister-in-law to pay you back the cost of a restaurant meal. In fact, you’d probably be outraged if she did so.

In the world of market norms, the situation is the opposite. You don’t expect your employees to work simply out of their good will. You don’t work for free yourself, no matter how nice of a person you are. The situation with two norms seems clear and simple for approximately two seconds. Then you quickly realize that it’s not.

How this affects us

Living in the world of two norms doesn’t come easy to us. We get confused and frustrated trying to apply each norm in the appropriate situation. The saying “It’s just business” has become a marker of a terrible person, because surely, you can’t just fire a worker that is also your best friend since high school in the same way you’d fire anyone else. Similarly, you can’t hire the aforementioned sister-in-law and expect her to work for less money. In his book Predictably Irrational, Dan Ariely reminds us how confused we get when it comes to sex. The guy might take the girl out a couple of times, pay for everything this includes, and get properly frustrated when the girl wouldn’t at least passionately kiss him. The emotions run high: his wallet is getting thinner, and there’s no way he can mention that to the girl without implying that she owes him sex. He knows she doesn’t, this isn’t prostitution where the rules are clear, but aren’t there any rules at all?

Social vs Market norms: research

In behavioral and marketing research, the confusion of the two norms has been studied with the utmost interest. Ariely and his colleagues have done massive amount of research to show the difference between the two and draw logical conclusions from those. First, they conducted the dullest fake study in the world (one had to drag circles on a computer) and asked three groups of students to do the task.

The first group was offered $5, the second group was offered 50 cents, and the third group was asked to do the task for free as a social favor. Then the researchers measured how hard the groups worked.

Those who received five dollars dragged on average 159 circles, and those who received 50 cents dragged on average 101 circles. More money caused participants to be more motivated and work by about 50% harder. What about the ones that worked for free?

On average, they dragged 168 circles, much more than those who were paid 50 cents, and slightly more than those who were paid five dollars.

I mean, surely, 50 cents isn’t a lot of money, but it’s something. Some sort of reward. A candy to go with your coffee. It’s still worth something, unlike the hours spent working for free. And yet, those who worked for free beat those who got payed.

This isn’t the only example and it doesn't just happen inside the laboratory, in other words not in real life. When AARP asked local lawyers if they would offer less expensive services to retirees at need, at something like $30 an hour, the lawyers refused. When the program manager from AARP had a brilliant idea and asked the lawyers if they would offer free services to needy retirees, they overwhelmingly said yes.

Why do people work better when they work for free?

You’d say that’s because people work for a cause (e.g., helping elderly, supporting scientific research) more willingly than they work for the money, and you’d be right.

However, seems like “the cause” disappears from their mind when they’re offered money (e.g., 30 dollars that the lawyers were offered). They quickly forget that they’d do it for the needy elderly, they simply assess the price and realize that this is too cheap.

When people are asked to help, the financial side isn’t there to distract them from the cause. The norms move from the market ones to the social ones, where it’s good and worthy to help just for the sake of helping. The same happened with students who were dragging circles for science. Once the small price of 50 cents was introduced, they felt like the effort is not worth the money. The idea of doing good never got the chance to enter their mind and motivate them.

What about gifts?

Another thing that researchers decided to test before drawing any conclusions was gifts. Do they fall under social or market norms? Do they hinder the performance or make it better?

To test that, researchers replicated the boring task of dragging circles. The results were interesting, to say the least. It didn’t matter whether they offered a snickers bar or a box of Godiva chocolates or asked participants to do the task as a social favor. In all three cases, people gave their best (moved the maximum amount of circles). However, when participants were told that their reward would be a Snickers bar worth 50 cents/a box of Godiva chocolate worth 5 dollars - then the results were exactly the same as with monetary rewards of 50 cents and 5 dollars.

Seems like gifts are seen as a part of the social world unless we’re reminded that they cost money.

Beyond completing the task

The world of social norms and the world of market norms are different in their cores. Market implies individualism and self-reliance, while social world implies collectivism and support. This was the hypothesis and it was shown to be correct: participants that were primed to think about money (and consequently moved into the world of market norms) were less likely to help a stranger, to work as a team, and less willing to communicate.

Marketing takeaways:

Now you might be thinking that this is all very interesting indeed, but what the hell are you supposed to do with this information. Well, hear the researchers and me out: there’s a lot to be taken from these studies.

1. On the company’s relationship with its customers

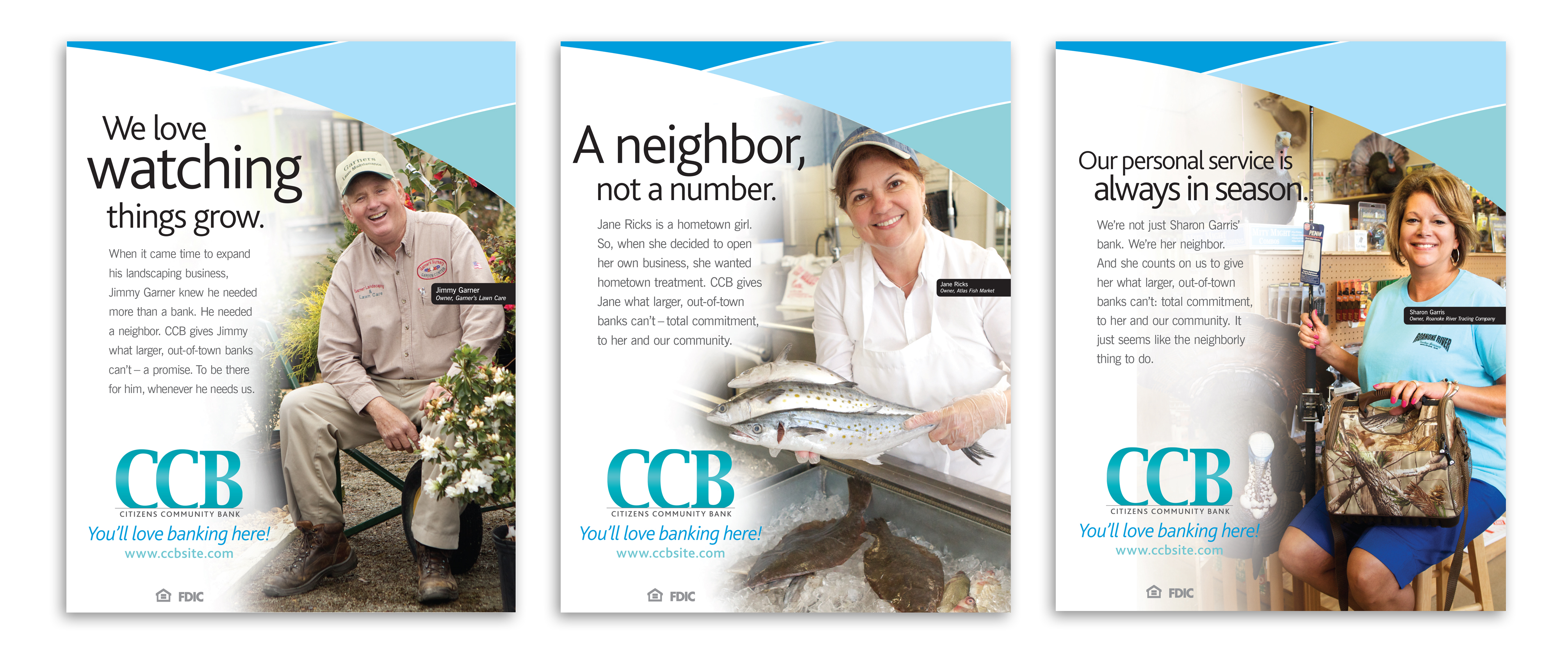

It’s an ongoing trend to try and build a social relationship with your customers. Banks and other huge corporation pour in billions of dollars into advertising campaigns that proclaim that they are pretty much your neighbours; that you can lend money at any time; that they’ll help you build your house because you are friends. These companies do their best to see them as a part of your social world.

This is all good: you feel like you can trust the bank, you forgive some minor problems they have, they help you out and suggest the genuinely best possible deal. This is all good until something goes wrong. For example, the bank charges a fee for something. And then all hell breaks loose: the fee is a relationship killer, a stab in the back. You can’t trust them anymore, you change the bank “that at least doesn’t lie to me”.

Meanwhile, in the market world, a fee would be an acceptable thing to a customer. It’s part of the deal that you both agreed to, it’s business. It doesn’t feel personal and doesn’t offend the customer in any way.

As a brand, you have to treat your customers the same way over time. You can’t be a family to them one day and become an impersonal corporation with its strict rules the next day. This will lose you customers and create terrible and unfair word-of-mouth. To avoid that, make it clear in your ads and campaigns that you’re a good, trustworthy, experienced, etc. company - but don’t follow the trend, don’t pretend to be a friend.

2. On the company’s relationship with its employees.

The second ongoing trend is to build a social relationship with your employees. This makes even more sense: you don’t only want your employees to work well. You want them to communicate, work in a team, help each other, as well as be passionate and engaged with what they do. Moreover, the nine-to-five business day is gone, and we all know employees often continue working when they are off their working hours. Why do they often do it? Because they feel that they are in the world of social norms.

Unlike with the customers, it’s often possible to keep the social relationship within the company coupled with the market one. However, the rules stay the same meaning that it has to be a long-term commitment. If employees work extra, reply to important tweets on weekends, go to meetings in a moment’s notice, and so on, the company is trusted to do something extra - like offer support when they are sick, or childcare. It’s a social exchange: both parties trust each other that they’d try to help when things go awry.

It’s also worthwhile to think of the way companies reward employees. Even though if asked, every person would prefer monetary reward, the things that facilitate social norms are gifts and benefits. The company becomes then something bigger than a place that gives money in exchange for effort, it becomes also a place that cares about the employee, and this calls for reciprocation. That’s what many startups, ex-startups like Google, open-source software, etc. do that makes them a dreamy place to work for and get them employees that eat, sleep, and get married within the company.

Conclusion:

As said before, it’s hard to live in the worlds of both norms that theoretically shouldn’t collide, but in reality do that all the time. It leads to us doing “the social dance”, trying to keep the balance, to be fair and not to offend anyone. But there’s also something very specific to be taken from this research.

First, it’s essential to understand that people work well for a reasonable wage and people work well (even a bit better) for free. But offer an inadequate pay, and they will do a terrible job.

Second, as a business you should stick to one of the worlds. You’re either a friendly local coffee shop that doesn’t mind the customer paying back the next day or a corporation that will charge the customer if she’s late with her payment. You can’t have it both ways.

Third, money can’t buy you love. You’ll have employees doing a good job if you pay them well, however, they’ll walk away and do an equally good job somewhere else if they pay them better. If you’re after loyalty, passion, and collective values - you’ve got to enter the world of social norms and reciprocation.